The debate over the accessibility of medical interventions for minor children who identify as “trans” continues to heat up in Canada. Pierre Poilievre was asked a very direct question yesterday in a media scrum “You’re against puberty blockers for children under 18?” “Yes” was his answer.

He said adults should have the freedom to make their own choices concerning medical gender interventions such as hormones. His position on gender medicalization for minors, however, is now clear: children need protection so that they can “make adult decisions when they become adults”.

Canadian Gender Report welcomes the clarity of this position and agrees that children require protection from experimental medical interventions such as puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones and gender surgeries. An opinion, however, is hardly enough.

Sweden, Finland, the UK, Norway and Denmark have all recently announced more restrictive access to these medical interventions, often referred to as “gender affirmation care”. In particular, Sweden and the UK have recognized the experimental nature of these treatments and in the exceptional cases where puberty blockers are permitted to be used on under 18’s, there are strict research protocols that need to be followed so that health outcomes can be tracked and patient follow up is ensured. It is time Canada implemented similar protocols.

The pendulum has swung too far in Canada in favour of on-demand and “child-led” access to medical gender interventions. The evidence to support these invasive medical interventions is of such poor quality that all systematic reviews of the evidence have concluded that the risks may outweigh any benefits. There are simply too many unknowns to be subjecting vulnerable young people to irreversible medical treatments when they can be supported with psychological services and wait until adulthood as a very reasonable alternative.

How did we get here?

Usage of puberty blockers in Canada began in 2005, less than 20 years ago. The CAMH Gender Identity Disorders clinic in Toronto was the first clinic to introduce them, under strict cautionary principles, and after much assessment and reflection with their young clients to try to determine whether they would be in a young person’s long-term best interest. Parents were an integral part of this decision-making process.

The founder of the CAMH GIDS clinic, Dr Susan Bradley, told us in an interview that her clinic started using puberty blockers with children who had a long history of gender dysphoria. A young person needed to be 16 before they were even offered puberty blockers. She said that the clinicians really had nothing but a “gut feeling” to go on and that they had adopted the usage of puberty blockers based on the Dutch protocol, which presented puberty blockers as reversible.

Soon after, medical societies started to produce guidance for the usage of puberty blockers based on the initial Dutch study of 55 young people (this cohort all presented with persistent and consistent early-onset childhood gender dysphoria, unlike many young people seeking gender transition today). Societies such as the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Endocrine Society endorsed this protocol on the belief that these kids were suicidal and that these interventions were life-saving. At the time, they also believed that puberty blockers were a “pause button” and fully reversible. Notably, the American Academy of Pediatrics has announced they will conduct a review of the evidence on gender-affirming care. Their current guidance in favour of “gender affirmation” was developed despite much evidence that most children grow out of their assumed gender personas once they complete puberty.

The Dutch government announced last year that they will be re-evaluating treatment protocols for puberty blockers and hormones in children.

62% of kids are now offered puberty blockers at their first visit to a Canadian gender clinic

Puberty blockers are being offered to children at the first visit to a gender clinic in 62% of cases, according to recent research conducted by the Trans Youth Can team. Many gender clinics have adopted the policy of offering puberty blockers at a first visit. This is in line with a coinciding trend to eliminate the need for mental health assessments.

The study methodology recruitment parameters identify that these youth have been referred for hormones. This is the way that children and teens can access gender clinics in Canada. The “Generalizability” section of the study states: “The study population is likely representative of youth <16 years of age referred for hormonal suppression or hormone therapy to specialized medical clinics in Canada. We included all major clinics providing such care during the study period. Although recruitment period varied by clinic, we weighted results to remove this potential bias. Some community clinics, family doctors, and general pediatricians have begun providing hormonal suppression for younger youth, including those in rural areas, often in consultation with subspecialists; such youth are not represented in this study”.

Under “Clinic Visit Outcomes” – the description just above Table 4, it states “Of 46 participants not prescribed hormones at this visit, physician’s reason was included in 36 records. The most common reason was the clinic protocol of not prescribing at first visit.” (emphasis ours) The paragraph here goes on to detail other reasons youth do not receive a prescription on their first visit to a gender clinic in Canada; these can include “fear of needles”.

Yes, puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones are being offered to children and teens at their FIRST visit to a gender clinic. Here is one account from a parent of a now-desisted teenage girl who was offered puberty blockers at her first appointment at the Sick Kids gender clinic.

When gender clinics are questioned about their usage of puberty blockers and other hormones, they’re quick to make claims that “comprehensive assessments” are conducted. But we question how this is possible given that 2/3 of children are offered these hormones or hormone blockers at their first visit.

What’s changed in the past 20 years?

Since puberty blockers were first introduced as a potential treatment pathway several developments have transpired that create an extreme level of risk today for children and young people who are gender non-conforming.

- The previous protocol of “watchful waiting” was replaced with “gender affirmation care”. Gender affirmation is becoming synonymous with on-demand access to puberty blockers and other medical interventions based upon a child’s declared gender goals. The term “assessment” meanwhile, has been hijacked to mean very different things. Mental health assessments are considered “stigmatizing” and “gate keeping”. The assessment process today in Canada is primarily to assess capacity to consent.

- Gender affirmation care has been framed in human rights terms. “Trans rights are human rights” is the mantra we hear when anyone questions how children in schools or healthcare can transition without question. This has led to a social justice perspective that is blind to what Canadians expect from their healthcare systems – a cautious evidence-based medical perspective that values balancing the risks of very serious medical interventions against potential benefits to assess whether these interventions are appropriate.

- The cohort of young people presenting to gender clinics has changed. 20 years ago it was overwhelmingly pre-pubescent boys who asserted from a very young age that they were girls. Now, gender clinics are overwhelmingly seeing adolescent females, many of whom are declaring a “non-binary” identity but nonetheless wish to have their breasts removed or stop their period.

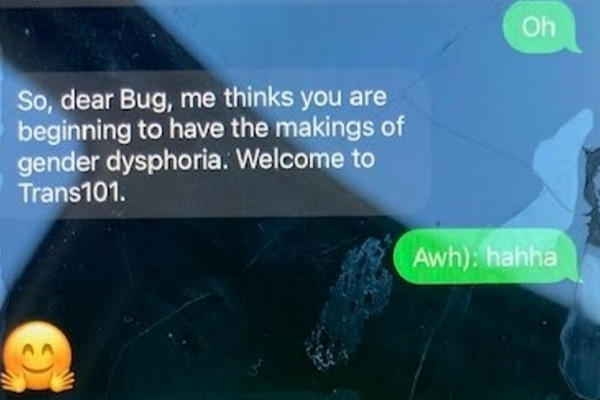

- Social media and the human rights movement that has taken on trans-rights as the next social justice fight has influenced society and young people in general. Young people on social media can be easily influenced down “rabbit holes” to believe that their worries are related to their gender. As a society, we seem to agree that social media can be harmful to young people and there are studies indicating it can influence teens to self-diagnose themselves, including Tourette Syndrome and Disociative Identity Disorder. Why is it so hard to believe that young people are similarly being convinced via social media and peer influence that they’re “trans”?

- Language has changed. Consider that 20 years ago, the word “transgender” was unknown. Trans rights activists prefer the word “transgender” to “trans-sexual”. Transgender is certainly a much easier term to apply to children. Queer culture seeks to disrupt norms and eliminate the gender binary. The current mania enveloping the western world is primarily driven by the celebrity status given to queer culture rather than a measured and thoughtful approach to protecting the small minority of mostly males who live as trans-sexuals (many of them not seeking “bottom surgery” at all!)

- Misinformation. Higher risk of suicide is often touted as the reason why gender affirmation medical interventions need to be made easily accessible, but this claim is not substantiated by the current best available evidence. In addition to this baseless threat, what’s particularly concerning is that the information given to young patients when they provide their “informed” consent to these medical procedures is not accurate. For example, informed consent forms will state that the rate of regret is very low (under 1%) but this data is not accurate because health outcomes are not being tracked. We simply do not know the rate of regret although current estimates are that approximately 30% of patients will detransition or discontinue medical interventions for various reasons.

- Institutional capture. Unfortunately, our medical societies and psychological associations have been captured by the “affirmation” culture. It is extremely disappointing that the leadership in these associations does not take a hard look at the evidence and reconsider their positions. The AAP, which represents pediatricians in the US and Canada has finally agreed to review the evidence after mounting pressure that their “gender affirmation” guidelines lack appropriate evidence. The CPS and AMA in Canada have both issued letters recently in support of gender affirmation care, however, these include serious flaws that will be addressed in a public letter in the coming days.

Conclusion

Canadian Gender Report welcomes the clarity of Poilievre’s position and agrees that children require protection from experimental medical interventions such as puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones and gender surgeries.

Poilievre’s statement, however, is merely an opinion. What needs to happen is the creation of evidence-based guidance for the usage of such invasive medical interventions across Canada. The evidence behind these interventions does not support their unfettered use on children and other countries such as Sweden have recently created strict research protocols under which they can be used. A similar approach in Canada is urgently needed.

The medical profession, unfortunately, has not provided sufficient evidence or even a willingness to track health outcomes to determine whether these interventions are safe and lead to long-term benefits. The State must therefore act to regulate whether access to these interventions is in the best interest of children.

It’s time to take a step back and re-evaluate how our schools and our healthcare systems are supporting these vulnerable young people through the difficult stage of adolescence and ensure that well-intentioned clinicians and educators are not putting children at greater risk by funneling them down a path of irreversible medical harm.