Children who don’t conform to typical gender stereotypes often face challenges that affect their psychological well-being. A research team at the University of Toronto highlighted this fact in new research published last month in the American Psychological Association’s Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology.

Their study sheds light on the well-being of gender non-conforming children who haven’t yet socially transitioned. 162 children were carefully selected to form a sample that could be compared to the study samples used to recommend gender-affirming care in which social gender transitioning is often a first step. The children involved in the study met the criteria of showing a gender expression that is similar to the opposite gender in terms of traits like gender-related behaviour, play styles, and feelings, but their current gender identity aligned with their birth sex/gender.

The researchers confirmed that gender non-conforming children experience elevated behavioural and emotional challenges relative to gender-stereotypical children.

But, does social transitioning improve the psychological well-being of gender non-conforming children?

Transgender people who socially transition make others aware of their gender identity. They often adopt a new name to use in social interactions and ask people to use different pronouns when referring to them.

The interesting new discovery in this research is that the level of well-being for children who had socially transitioned was no different from those who had not.

“Overall, gender-variant children appeared to experience similar psychosocial challenges regardless of transition status.”, the researchers concluded.

The testing system included the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) and a number of measures for internalized anxiety and depression.

The new study wasn’t able to measure whether the practice of socially transitioning children to the opposite gender improves their level of well-being, but it raises some doubts about the research that is being used to advocate for this practice.

The UofT researchers called into question the results of the limited research used to push for gender-affirming care and social gender transitioning.

It turns out a previous study used to argue for the practice of social gender transitioning has some major flaws. Firstly, the study comparisons did not provide statistical controls (e.g., age and birth-assigned sex compositions of the samples). Secondly, the clinic samples were based on children seen “one or more decades ago”.

Of the study used to argue for gender-affirming care, the researchers said the risk of using outdated data is high given how acceptance of gender non-conforming children has increased in recent years. They concluded that “further research is needed to evaluate possible effects of childhood social gender transition on well-being”.

“Further research is needed to evaluate possible effects of childhood social gender transition on well-being”.

In addition to reviewing previous research on gender-affirming care models, the research team assessed peer support and parental support measures.

Peer relations was identified as a predictor of well-being among gender-variant children. They recommend that psychosocial challenges among gender-variant youth require monitoring “irrespective of transition status, and relationships with peers may be especially important to consider.”

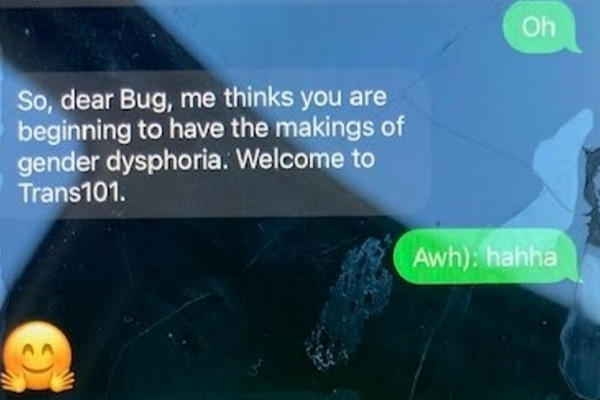

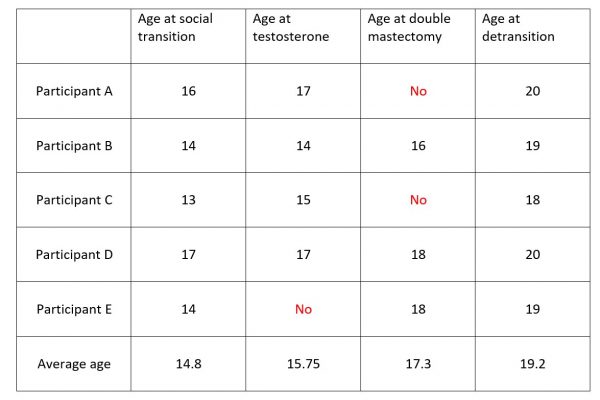

We’re grateful for this research and other ongoing efforts to better understand the challenges facing gender non-conforming children. We’d like to note that another possible interpretation of this research would be to assert that children who socially transition are no worse off for having done so. However, there’s also reason for concern that the pathway of affirmation and social transition leads more easily to medical transition and persistence of gender dysphoria.

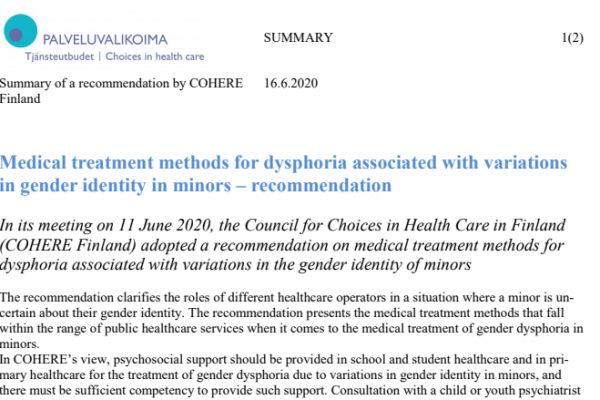

It would be interesting for researchers to study whether the practice of social gender transition has an impact on rates of desistance. Under the watchful waiting care model, research has shown that 85% of children will desist and become comfortable in their natal sex.

Ultimately, we’d like to understand whether more or fewer children require medical interventions under the gender-affirming care model and which model of care leads to better long term health outcomes.

I’d like the gender boxes to be broken open and discarded, instead of taking kids uncomfortable in one box and sticking them in the other one. A child should be able to wear whatever they like regardless of sex.

What an effective way of saying this, Julia. Break open the box and let us be, wear, do everything that encourages us to live well, as ourselves.