As countries around the world question the exponential increase in children and young people seeking medical gender transition we thought we’d try to pull together whatever data we could find on the trend in Canada.

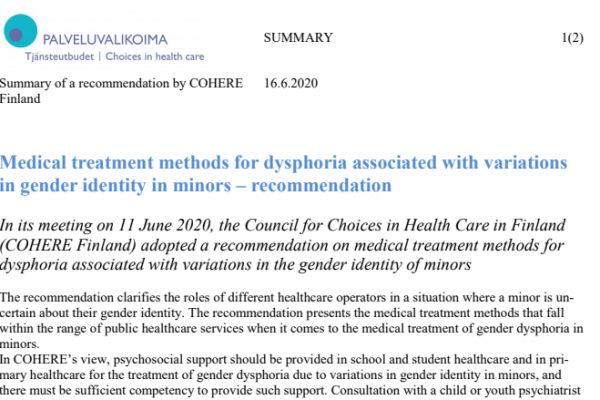

The news from Sweden this month that their premiere gender clinics for children and young people have stopped the practice of prescribing puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones for under-18’s and have instituted a clinical trial protocol for those young people (believed to be above age 16) to access medicalized gender transition is a signal to clinicians that the days of medical experimentation on children are numbered.

It’s very difficult to get good Canadian data on the number of children and young people being affirmed and medically transitioned because our healthcare system is managed provincially, and the data is not readily available.

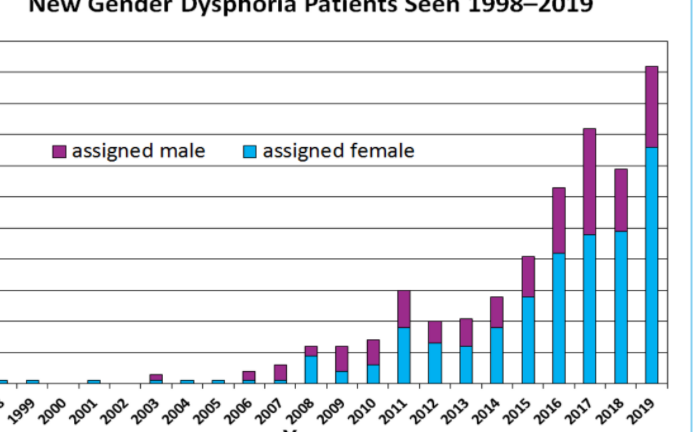

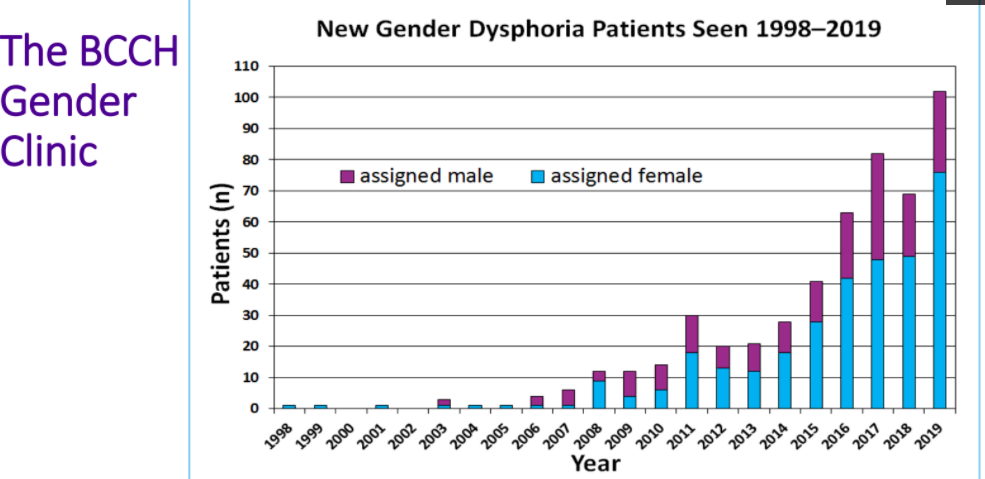

However, based on data from several major gender clinics, we now believe that Canada is witnessing a 10x increase in children and young people being referred for medical transition in the past 10 years.

BC Children’s Hospital, SickKids Hospital, and CHEO (Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario) are all reporting a 10x increase in referrals over the past 10 years. At most clinics, the numbers of referrals are doubling every few years, if not faster than that. Further, new clinics have been created in this period. The exponential growth is unprecedented.

Source: https://transyouthcan.ca/results/vancouver-self-care-and-coping-webinar/

TransYouth Can report on referrals to gender clinics up to 2016:

Metta Gender Clinic in Calgary (Southern Alberta) is now following approximately 500 youth.

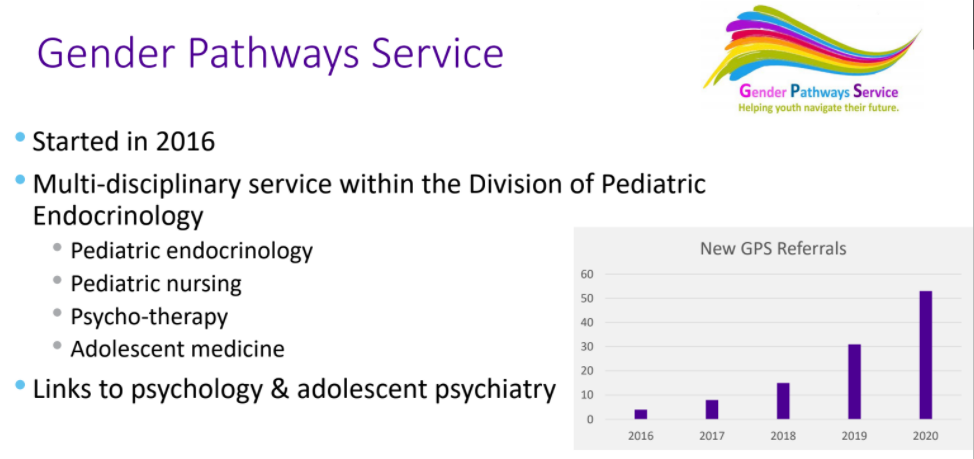

Referrals to the Gender Pathway Service in London Ontario have doubled in the past 2 years:

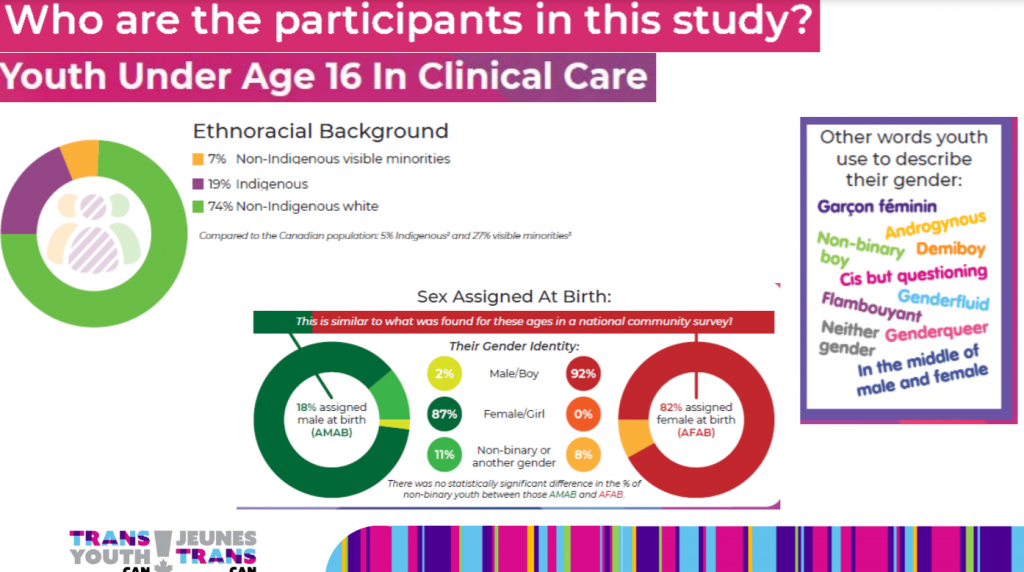

Characteristics of youth being referred to gender clinics in Canada include an extremely high proportion of indigenous youth (based on this study report) and a disproportionate number of natal females.

19% Indigenous youth participating in a study on puberty blockers seems like an extremely disproportionate number. We understand that the Two-Spirit tradition in indigenous cultures reflects an important and different cultural understanding of gender, but this Indigenous tradition has never included invasive medical procedures until now.

Also of interest is that the field in Canada is moving away from the more clinical view of “gender dysphoria” to enable treatment and medicalization for “gender distress”:

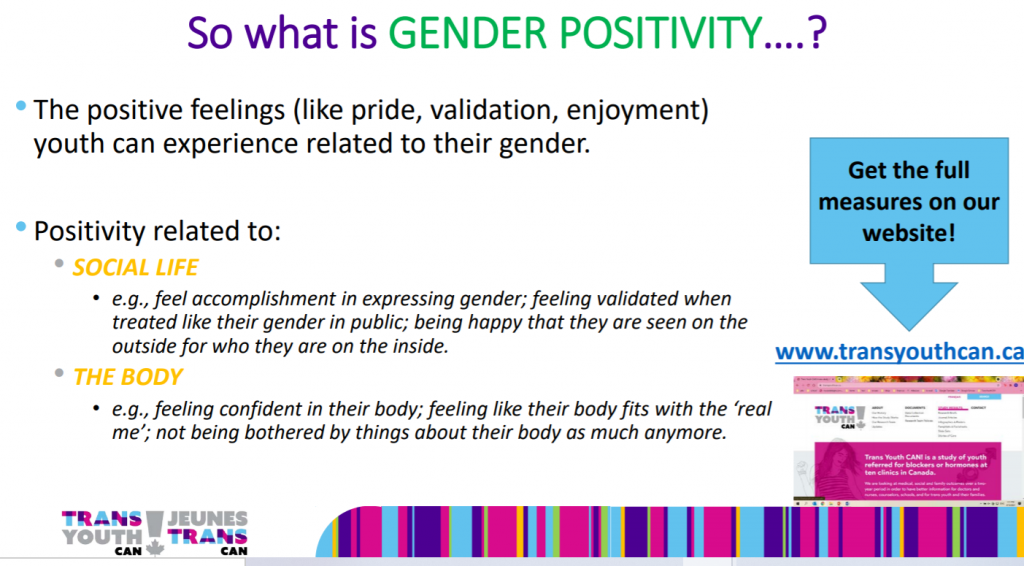

The desired outcome is “gender positivity”:

Medicalization and Consent to Treatment

While many of these clinics have mental health professionals and social workers on staff, parents report to us that these professionals are not on staff to provide counseling outside of medicalization options. For example, children and young people are not being offered an alternative to medicalization in the form of talk therapy in order to manage their feelings of gender distress. The only options they are being offered to manage gender distress are medicalization with puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. The social worker and mental health staff at the gender clinics appear to be there to support this medicalization process, rather than establish whether medicalization is in the best interests of a young person based on their individualized needs. The protocol that is being followed (according to SickKids Hospital) is one where young people choose their medicalization “gender journey” based on their self-directed gender goals.

While gender clinic professionals assert that there are “comprehensive assessments” being done, these are called “hormone readiness assessments” and are undertaken for the sole purpose to document that a young person is consenting to medical transition.

A recent survey of 237 detransitioners (including 15 Canadian participants) revealed that 45% of the sample reported not feeling properly informed about the health implications of the accessed treatments and interventions before undergoing them. A third (33%) answered that they felt partly informed, 18% reported feeling properly informed, and 5% were not sure. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00918369.2021.1919479

Whether patients are being properly informed of the risks and alternatives for care is likely being exacerbated by the position held by the professional association CPATH, the Canadian Professional Association of Transgender Health, who consider any involvement from mental health professionals to be “stigmatizing” and “pathologizing”. Removing barriers to medicalization options, regardless of age, is the only pursuit of this group. The result is that CPATH and Canadian gender clinics have adopted or are in the process of adopting a consent based treatment model.

CPATH holds the position that a more responsive informed consent model of care gives patients permission to accept or decline possibly stigmatizing diagnoses as well as potential treatments that are available to them, while ensuring gender-affirming care is accessible in an environment that expresses respect for patient autonomy. The informed consent model offers less dependence on health professionals in a “gate-keeping” role that has been perceived as unnecessarily pathologizing and may limit access to care.

See page 3: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Brief/BR10482210/br-external/CanadianProfessionalAssociationForTransgenderHealth-1-e.pdf

There is an underlying assumption that the child knows what they want and need, in terms of medicalization options in order to transform their body to reflect their “gender goals” (a term used by SickKids Hospital).

The Health Care Consent Act of Ontario defines the elements of consent as:

Elements of consent

11 (1) The following are the elements required for consent to treatment:

1. The consent must relate to the treatment.

2. The consent must be informed.

3. The consent must be given voluntarily.

4. The consent must not be obtained through misrepresentation or fraud. 1996, c. 2, Sched. A, s. 11 (1).

Further, for the consent to be informed the information provided must include , from 11(2) and 11(3):

1. The nature of the treatment.

2. The expected benefits of the treatment.

3. The material risks of the treatment.

4. The material side effects of the treatment.

5. Alternative courses of action.

6. The likely consequences of not having the treatment. 1996, c. 2, Sched. A, s. 11 (3)

Conclusion

Provincial legislation on consent outlines that individuals must have the capacity to consent, that consent must be informed, and that the treatment must be in the “best interests” of an individual, as determined by healthcare professionals. It’s not clear that Canadian children and young people are being properly informed of the risks of treatment and they are never informed about alternative treatments, such as talk therapy.

Children’s hospitals in Sweden, and the High Court of Britain have determined that the test for consent cannot be met. What rationale do Canadian gender clinics have to justify that their process is somehow sufficient?