Desistance rates of 85% are typically cited for children who experience gender dysphoria and end up being comfortable in their natal sex, without the need for medical interventions. This desistance rate is based on data collected prior to the gender-affirming care model being advocated for transgender health, in an era when watchful waiting and other gatekeeping models were in place for youth experiencing gender dysphoria.

“To date, the prospective follow-up studies on children with GD, for whom the majority would meet the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for Gender Identity Disorder (GID) collectively reported on the outcomes of 246 children. At the time of follow-up in adolescence or adulthood, these studies showed that, for the majority of children (84.2%; n= 207), the GD desisted.”

Steensma, T. D., Mcguire, J. K., Kreukels, B. P., Beekman, A. J., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T.(2013).Factors Associated with Desistance and Persistence of Childhood Gender Dysphoria:A Quantitative Follow-Up Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & AdolescentPsychiatry,52(6), 582-590.

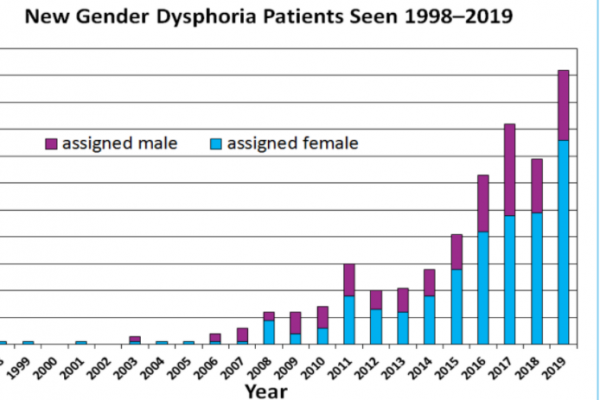

In recent years, gender-affirming care has been advocated by WPATH (World Professional Association for Transgender Health) and has been endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in their policy statement Ensuring Comprehensive Care and Support for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Children and Adolescents. Gender-affirming care involves social gender transitioning in which individuals adopt new pronouns, change their name, and express themselves by dressing or adopting other characteristics of the opposite sex.

“There are several components (to gender-affirming care), which include social affirmation, legal affirmation, psychological affirmation, medical affirmation, and surgical affirmation.” according to Alex S. Keuroghlian, MD, MPH, director of education and training programs at The Fenway Institute at Fenway Health in Boston and assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

Some clinicians, however, have expressed concerns with the gender-affirming approach and are beginning to speak out about its impact on children. Marcus Evans, former Governor of the Board of Governors at the UK’s Tavistock clinic for GIDS has become one of the most vocal critics of the gender-affirming model.

“The affirmative approach to children with Gender Dysphoria fails to provide a therapeutic space for thorough assessment exploration and thought.”

Marcus Evans, Former Governor, Tavistock GIDS clinic, UK

All this brings us to the million-dollar question: does gender-affirming care, in the form of social gender transitioning, have an impact on desistance rates for gender dysphoric youth? What does the available evidence tell us?

Desistance rates and social gender transitioning

Ken Zucker, Ph.D. C.Psych and Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto presented a discussion of the differences in developmental trajectories for children with gender dysphoria at the 24th Congress of the World Association of Sexual Health, in October 2019, Mexico City. The following information is summarized and quoted from his presentation.

Dr Zucker based his analysis on a review of a number of follow up studies for persistence and desistance rates. He categorized therapeutic approaches designed to reduce gender dysphoria into 3 different types:

- Treatment 1: Assessment, “watchful waiting”

- Treatment 2: Assessment, active treatment of many kinds (recommendations to parents to implement in the naturalistic environment, behavior therapy, play therapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, group therapy, etc., etc.)

- Treatment 3: Gender Social Transition

“The follow-up studies summarized so far, by and large, collected data on children who were assessed (and sometimes treated) prior to the emergence, around the mid-2000s, of pre-pubertal gender social transition as an alternative type of psychosocial treatment designed to reduce gender dysphoria: a treatment that parents may have instituted on their own, in consultation with a clinician, or on the advice of a clinician or some other type of professional (e.g., a teacher).”

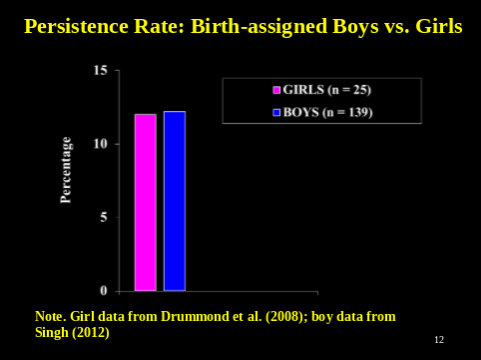

The very low persistence rates in the case of Treatments 1 and 2 show that gender identity becomes more congruent with birth-assigned sex in the majority of cases.

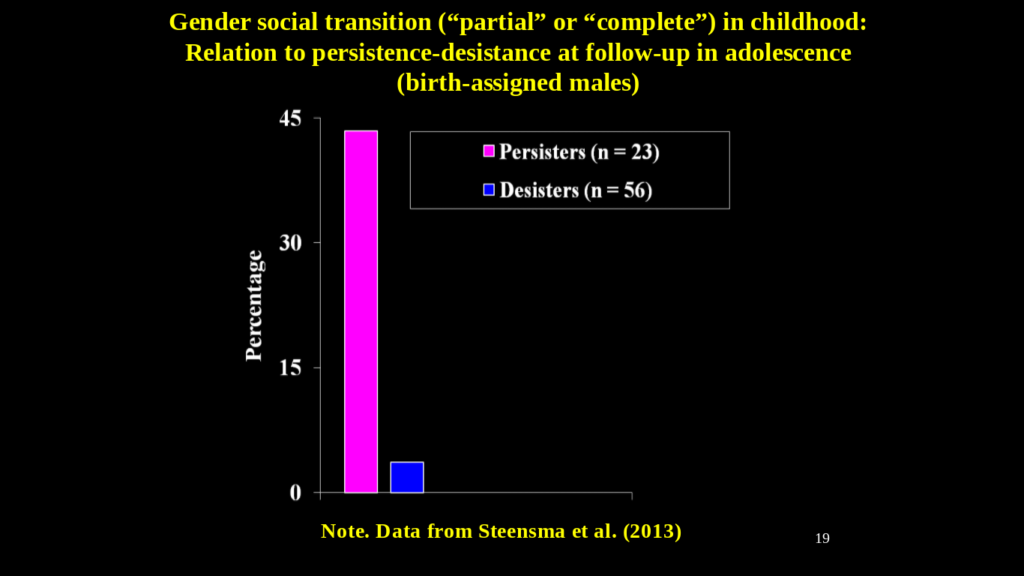

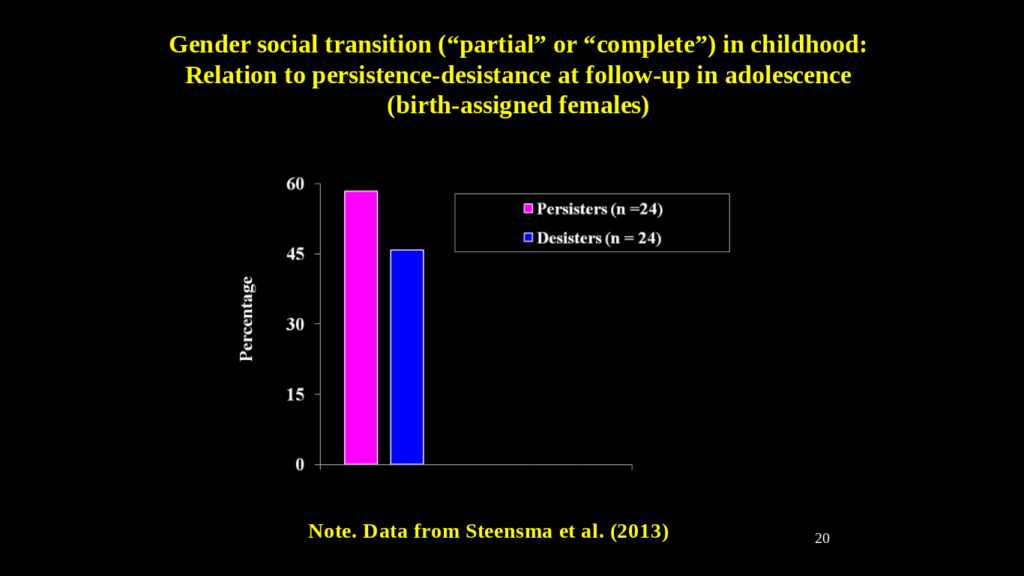

To compare the persistence and desistance rates of children who received a gender-affirming care approach characterized by social gender transitioning, Dr Zucker used data from Steensma et al. (2013) which reported a systematic follow-up study of children in which some children were classified as having had either a partial or a complete social transition prior to puberty.

The relationship between social gender transition and the follow-up persistence and desistance rates is striking. Among desisters, almost none of the natal boys had socially transitioned. Almost 45% of the persistors, however, had partially or completely socially transitioned, yet their gender dysphoria had not resolved.

Social transition in relation to persistence and desistance was not as strong among the girls. Almost 60% of the persistors had socially transitioned. A significant number of desisters had socially transitioned as well, although Dr Zucker cautioned that the definition of social transition used by Steensma probably captured some girls where the social transition metric may have been very broad (e.g., change in hair-style or clothing style).

Dr Zucker predicts that as new samples of socially transitioned children become available, the rate of persistence will be much higher when compared to the older studies, where most of the children received either Treatment 1 or Treatment 2. Of the 3rd type of treatment, social gender transition, he commented that it offers a different approach that leads to desistance: the gender dysphoria dissipates because the child is now living in the “desired” gender; however, for desistance to remain stable, it will often, if not always, require biomedical treatment (life-long hormone therapy with or without gender-affirming surgery).

There are many possible pathways to desistance, which leads to the parental conundrum: which therapeutic approach does one take to reduce gender dysphoria? This is what the contemporary parent (and clinician) must decide.

What is in the best interest of the pre-pubertal child with gender dysphoria is very hotly contested: (1) an early gender social transition; (2) “watchful waiting”; (3) psychoeducation; (4) developmentally-informed therapy (DIT).

I do not believe that any of these approaches needs to be privileged over the others until we have more data. I also do not believe that any particular psychosexual outcome needs to be privileged over others—on this point, other kinds of data are required.

Ken Zucker, Ph.D, C.Psych

Zucker, K. J. (2019). Different strokes for different folks. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Journal.

In the best interest of the pre-pubertal child: where do we go from here?

Mental health care and counseling has always been a gap in our healthcare system in Canada, and we expect, around the world. Many trans-supportive clinicians call for more mental health services to support trans kids, however, where those services have been documented and reported on to date they are being used to support the process of medical transition, rather than being considered a valid alternative treatment pathway.

For example, the DeVries study (2014) Young Adult Psychological Outcome After Puberty Suppression and Gender Reassignment published in the Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics, provided intensive counselling for gender-dysphoric youth, but only in the context of medical transition. This study concluded that “a clinical protocol of a multidisciplinary team with mental health professionals, physicians, and surgeons, including puberty suppression, followed by cross-sex hormones and gender reassignment surgery, provided gender-dysphoric youth who seek gender reassignment from early puberty on, the opportunity to develop into well-functioning young adults.”

The major problem with this study, however, is that it offered no control group to assess whether intensive counseling and alternative forms of therapy that did not involve medical interventions would yield similar results, or in fact, measure the degree to which the positive outcomes of this study could be attributed to the intensive counseling regardless of hormone and surgical affirmations.

We continue to be concerned about the push for gender-affirming care because, in practice, it appears that physicians providing this kind of care are more likely to offer medical interventions as part of their standard protocol rather than first allow for therapeutic approaches. Parents and detransitioners often make this observation.

It makes sense that there are possible interactions that occur when different therapeutic approaches are pursued, and more research needs to be done to understand the psychosocial factors that contribute to different outcomes.

Further, it’s important to recognize that the trans-activist community demands of trans-supportive researchers and clinicians that they work from a starting point that medically transitioning, in and of itself, should never be considered a bad outcome. Are they, therefore, unduly influenced to prove that the gender-affirming medical pathway to desistance leads to favorable outcomes.

In this extremely politically charged environment, parents, detransitioners, and a growing group of whistleblower clinicians are speaking up with grave concerns over this unquestioned treatment pathway for gender non-conforming youth.

By a growing number of accounts, it seems our healthcare system has embraced gender-affirming care as the holy-grail for transgender health without the necessary confidence that the best interests of children will be safely considered under this narrowly defined therapeutic framework. Other approaches, such as developmentally-informed therapy, watchful waiting and so on need not be relegated as “outdated” and “ineffective” (as they were in the highly controversial and disputed AAP policy statement) should the evidence of long term desistance and well-being prove otherwise.

Is the intensity or other experienced characteristics of gender dysphoria related to both the likelihood of social transition and desistance?

It would be helpful if you defined desistence and persistence. In the first part of this report it seems desistence is going back to natal sex and persistence is wanting to transition one’s sex.

But I can’t make sense of this sentence, “ Of the 3rd type of treatment, social gender transition, he commented that it offers a different approach that leads to desistance: the gender dysphoria dissipates because the child is now living in the “desired” gender; however, for desistance to remain stable, it will often, if not always, require biomedical treatment (life-long hormone therapy with or without gender-affirming surgery).”

Wouldn’t the third type of treatment lead to persistence if he is saying lifelong hormone therapy and gender affirming surgery would be needed? I thought the charts were showing a reversal in the trend of desistence using the third method compared the the first and second.